This may well be the most insightful and, dare I say, creative post I have written in the 14+ year, 350+ post history of the Bowlby Less Traveled blog. Before I explain why, a bit of housekeeping.

In my last post I said that I would introduce you to the work of systems thinker Donella Meadows. I’ll save this introduction for a later post. In addition, upon reflection, I feel as if I did not properly flesh out the third example of a negative feedback loop presented in my last post: the example that focused on embodied cognition. I apologize for that. As fate would have it, I’ll touch on this example in this post. Regardless, I will cover it more thoroughly in the future. Let’s get started.

Since I wrote my last post I’ve had a chance to finish reading Elhhonon Goldberg’s book Creativity—The Human Bain in the Age of Innovation. Around page 128 or so, Goldberg mentions something that just about took my breath away. He mentions an interaction he had with a patient that dovetails brilliantly with the workings of the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI), considered to be the gold standard for measuring attachment functioning in adults. The workings of the AAI juxtaposed with Goldberg’s description of an interaction he had with a patient is what triggered an “aha moment” for me, one that I think is profoundly important, so much so that I “stopped the presses.” Let me start by describing Goldberg’s interaction, and then I’ll bring it back around to the AAI.

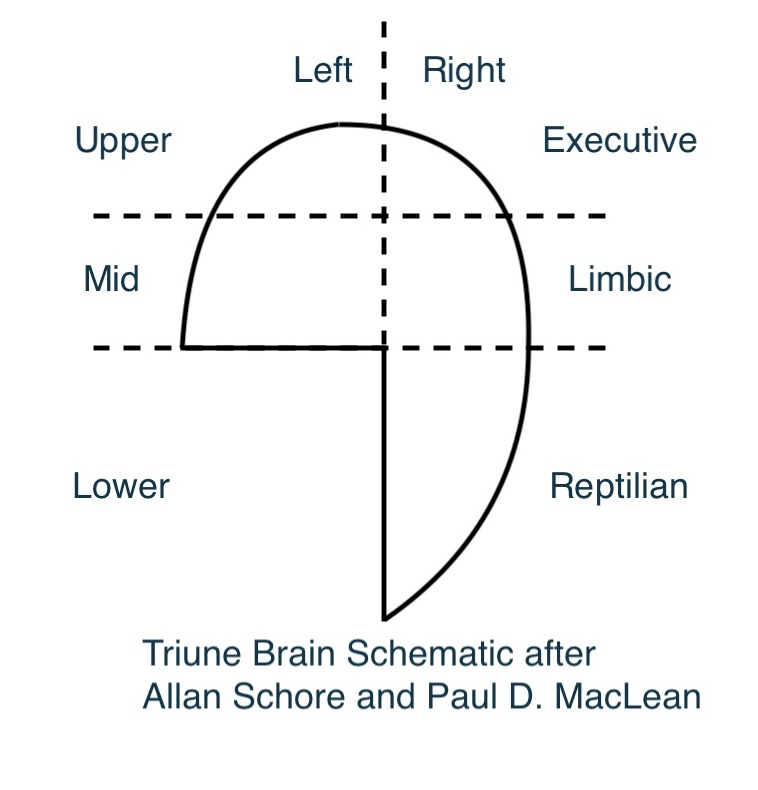

In what follows, I am stripping away significant amounts of neurological detail to facilitate understanding. It would help if you held in mind the simple three-layer model of the brain developed by Paul MacLean (and which I have modified here using work by Allan Schore).

The upper Executive brain is home to executive functions such as focusing attention, time travel (our sense of past, present, and future), mind-in-mind processes like empathy and Theory of Mind (ToM), and mental modeling (such as spatial cognition and cognitive maps). Goldberg talks about how the brain can shift into what he calls hyperfrontal states where the upper brain is working at full tilt boogie. “During hyperfrontal states [italics in original], the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is hard at work. It manipulates mental representations stored in the brain like Lego pieces, assembling them into new configurations through a deliberate goal-driven process …” writes Goldberg. He tells us that these hyperfrontal states become active “when we strain, consciously and deliberately, to solve a particular, well-articulated cognitive task at hand ….”

OK, so what happens when a “hyper” brain state is over, whether it results in a solution or not, and the upper brain enters a hypofrontal state?” Well, apparently the brain has what Goldberg calls a default mode network. Simply, once the upper brain shuts down and goes “hypo,” the default mode network becomes active. Interestingly, the default mode network turns its attention to the workings of the inner milieu, better known as the body.

It would seem that the default mode network plays a role in the hybrid nature of consciousness as talked about in my last post. As neurobiologist Antonio Damasio suggests, consciousness is at the same time part body or visceral experience, and part mind or conceptual experience. This hybrid of body and mind undergirds our understanding of cognition as being embodied. In essence, we think with our bodies as well as with our brains, which, after all is body. You simply cannot imagine the concept of “running” without engaging the motor-control systems of the brain.[1] It would appear that the default mode network allows the mind to move along the continuum that connects body and brain, that connects upper brain to the lower regions. In hypo states, the mind is allowed to just wander. “We can think of these [hypo] processes as undirected mental wanderings [italics in original],” writes Goldberg. He continues, “This is what a healthy individual probably experiences in sleep or in any dreamlike state, whether in trance or under hypnosis.” What happens when this back-and-forth dance between hyper and hypo states is disrupted? This is what happened when Goldberg asked a patient to engage in a relatively easy memory task.

Goldberg was working with a patient who lost significant portions of his upper brain as the result of an accident resulting in head injury. Goldberg told a very short story and then asked the patient to retell the story back to Goldberg. Here’s that story, the fable “A Hen and Golden Eggs” as told by Goldberg:

A man owned a hen that was laying golden eggs. The man was greedy and wanted more gold at once. He killed the hen and cut it open hoping to find a lot of gold inside, but there was none.

Using a tape recorder, Goldberg was able to transcribe the patient’s retelling of the above story. Here’s just a small snippet:

No gold at all … he cuts the hen more … no gold … the hen remains empty …. So he searches again and again …. No gold … he searches all around … in all places.

This monologue as Goldberg calls it, continues on eventually turning to a description of the workings of the tape recorder being used, which was then followed by a description of taking a bus to Bauman Square.

In analyzing the transcript, Goldberg noticed two patterns. The first pattern is characterized by what psychologists call perseveration. “The patient is ‘stuck’ in the same content, unable to move on,” Goldberg tell us. The second pattern is called field-dependent behavior. This cognitive behavior results when a person focuses on elements or objects in the environment that have no context to them. Goldberg allows that each of these patterns are often associated with damage to areas of the upper brain. Without the guidance of the upper brain, the lower brain regions are left to wander in an undirected, unfocused way.

In his work, Antonio Damasio talks about global amnesia. During global amnesia, a person can recognize a room and the objects occupying that room, however, they are unable to say how it is they got to that room or why that particular room is important to them. As a migraine sufferer, I have had experiences of global amnesia. It’s very disconcerting. During global amnesia, content is cutoff from context. So, how does all of this tie to the Adult Attachment Interview?

The AAI was developed by Carol George, Nancy Kaplan, and Mary Main starting back in 1984. Mary Main was one of Mary Ainsworth’s first PhD students. Ainsworth was John Bowlby’s longtime collaborator. She also developed the Strange Situation Assessment of attachment functioning in toddlers.

At the heart of the AAI is a focus on Grice’s Maxims of Conversation, which are quantity, quality, relation, and manner (pulling from the Wikipedia entry). Grice, a philosopher of language working back in the 1970s, put forth the idea that for a conversation to be effective and efficient, it had to adhere to four maxims of linguistic behavior:

- Quantity: Make your contribution as informative as is required (for the current purposes of the exchange).

- Quality: Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence.

- Relation: The information provided should be relevant to the current exchange and omit any irrelevant information.

- Manner: Provide information in an order that makes sense, and makes it easy for the recipient to process it.

To summarize, someone telling a story to another should be economical (i.e., do not be verbose), truthful (i.e., provide evidence), relevant (i.e., keep the information needs of the listener in mind), and organized so as to facilitate understanding.

Although I have heard Mary Main speak on at least two occasions at attachment conferences, I’m not sure how she and her colleagues (which included her husband Erik Hesse) arrived at the connection between attachment functioning, linguistic behavior, and brain functioning. Those of us in the Bowlbian attachment theory arena consider the development of the AAI to be sheer creative genius (the central topic of Goldberg’s book). As someone who has gone through the two-week training in how to administer the AAI, allow me to sketch out how it works.

From the outset, it is important to note that the AAI is designed to trigger and activate the attachment behavioral system. This differentiates it from other assessments of attachment, such as self-report questionnaires, that may or may not activate the attachment behavioral system. This may seem simplistic, however, if your goal is to assess the functioning of the attachment behavioral system, you have to make it, well, function. Similarly, the Strange Situation Assessment also triggers attachment functioning in the toddlers being assessed. This may appear manipulative, however, skilled psychotherapists will use the attachment bond that often forms between client and therapist to not only assess attachment functioning but to also move it from an insecure to secure attachment pattern (see the work of Louis Cozolino for more on this topic).

The AAI is a semi-structured interview designed to assess for attachment functioning in adults. The AAI does have a structure to it, but the interviewer is free to “go off script” to ask additional questions to elicit further information. After a brief period of getting to know one another, the interviewer (Ir) will ask the interviewee (Pt) to provide three words that describes the relationship Pt had with, first, his/her mother, and then his/her father. Typical words might be supportive, concerned, engaged, loving, present, playful, etc. Once Ir writes these words down, Ir will then ask Pt to describe what she/he did as a child of five or six when she/he became sick or hurt, maybe fell off a bike or became sick with a cold. This line of questioning is designed to activate the attachment behavioral system. This dialogue is recorded, not unlike the process that Goldberg describes. Once Pt is finished describing what she/he did when sick or hurt, Ir will then return to the three words asked for earlier. Ir may say something like, “Earlier, you said that the relationship you had with your mother/father as a child was ‘supportive.’ Could you give me a few examples from your childhood?” Here’s a coherent or “secure” answer (that I’m making up) that follows Grice’s maxims:

Thanks for asking. Looking back on the times I shared with my father, I experienced him as supportive because he would always come to my games, you know, cheer me on. I remember I wanted to run for class president, but the thought of it scared me to death. My father consoled me, told me that, yes, it would be a big commitment, but that he knew I could do it … but that it was my decision, and he would support me whatever I decided. I just remember him always asking, “How’s it going? You doin‘ OK?” You know, checking in with me. I guess that fits more with the “concerned” word I gave you [smiles]. Just so you know, my dad still supports me today, like with my decision to become a dentist. I do his teeth. I guess that’s me supporting him [chuckles]. Is that what you are looking for?

I’ll explain what’s going on with the above narrative in a moment. What follows is a response that might be coded as incoherent or “insecure” (again, made-up).

Yeah, did I say supportive. Yeah, she was so supportive, you know in that supportive way, always, always, always supporting me. There all the time. But, you know, you weren’t there when I needed you. Where were you when Danny and I were going through that rough patch. Nowhere! Right? Nowhere to be found. I’m doing it all here. I really could use your help. Supportive my ass! I … this is … [long silence] … sorry, what?

These are just two brief, made-up responses based on the types of real interviews I had to code during my training. And some of the narratives I coded would go on for two or three pages, not unlike the narrative Goldberg describes. So, what’s going on during an AAI interview?

By way of background, I took the AAI training probably in the early 2,000s. This was before there was much focus on what we now call Executive Functioning. We now know that the suite of executive skills includes focusing attention, time travel (our sense of past, present, and future), mind-in-mind processes like empathy and Theory of Mind (ToM), and mental modeling (such as spatial cognition and cognitive maps). In my opinion, what the AAI centrally assesses for is Executive Functioning. In this way, an early history of safe and secure attachment is associated with the development of robust EF skills later in life.[2] In contrast, an early history of insecure attachment is associated with a diminished capacity for Executive Functioning. Here are three examples of robust vs diminished EF as revealed by the responses above.

- In order to maintain Grice’s maxim of manner, one needs to be able to engage in mental time travel. This involves being able to keep straight past, present, and future, and to convey these timeframes to the listener in an orderly fashion. In the coherent narrative above, Pt keeps verb tenses straight and appropriate. The listener is able to move back and forth through time in a way that makes sense. In contrast, the insecure narrative reflects inappropriate and confusing timeframes, such as talking as if things that happened in the past are actually happening today, in the moment. Pt also moved from talking about her childhood to talking about problems she is having currently with her partner, Danny, without alerting the listener.

- In order to maintain Grice’s maxim of relation, Pt must be able to create a mental container for the mind of one’s self as well as the mind of the listener. In this way, Pt can compare what is being conveyed against the needs of the listener. By comparing mental models and by engaging in Theory of Mind, Pt is able to assess for relevance in an empathetic way. This also allows for an accurate assessment of appropriate quantity. Pt in the second response is not able to keep the mind of Ir in mind. The formation and maintenance of mental containers is central to mental time travel as we need to make comparisons between the mental containers representing past, present, and future. Appropriate use of verb tense reflects our ability to juggle different mental time containers.

- In oder to maintain Grice’s maxim of quality, Pt must be able to truly remember and access the past. Often insecure narratives will use adjectives and evidence that are glowing or over the top, such as “the best dad ever,” or “loved me so, so, so, much.” These appear to be placeholders for actual attachment relationships that did not happen, or happened ineffectually. These placeholders or “canned speech” are pulled from the expectations of society. The brain uses placeholders built from societal expectations to fill in the gaps in memories. Often an interviewee will simply say “I don’t remember” possibly reflecting dissociative processes used to protect the psyche at an early age.

I should point out that none of the above is necessarily a bad thing. A person may have legitimate reasons for being upset or angry with a parent our guardian who was not there either physically or emotionally or both. What we look for in AAI interviews is whether a person is able to reflect on these difficult past memories and keep them coherent within an appropriate timeframe. As an example, an interviewee could say something like, “No, my guardian was not there for me, and as a young child, that hurt. As a matter of fact, it still hurts today when I think back on it.” This is an example of metacognition or the ability to think about one’s thinking: yes, yet another Executive Function.

Speaking of quantity, I’ll leave it here and pick this back up in the next post where I’ll try to bring this back to neuropsychology and some of the observations that Goldberg makes. I think the genius of the AAI is its ability to use linguistic behavior as a way of getting at brain functioning, especially brain functioning in response to an activation of the attachment behavioral system. Goldberg knew that his patient had sustained damage to the upper brain, and, as a result, he could expect the linguistic behavior deficiencies he recorded. But it would seem that activation of the attachment behavioral system in a relational context can affect brain functioning in a way that mimics brain damage.[3] This is not a new or novel idea. It has been long known that people experiencing PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder) are prone to reliving experiences where the sufferer experiences past traumatic events as if they are happening today. Often this is what is happening in insecure narratives recorded by the AAI. And, as I will touch on in the next post, this retreat to lower levels of brain functioning when the brain is under assault is exactly what we would expect if we take an organic systems theory view of the brain. Evolution has provided us with “escape hatches” that help protect the brain from sustaining damage, dissociation chief among them. Unfortunately, as attachment researchers and practitioners will tell us, defenses used as a child that provided protection may become counterproductive when used as an adult. Come to think of it, was this not the same message Freud gave us? As a side note, Bowlby was immersed in Freud’s teachings specifically and psychodynamics generally before he moved in the directions of evolution, organic systems theory, ethology, developmental psychology, and attachment functioning. Teaser alert, this process of immersion will become important in the next post.

NOTES:

[1] This topic would normally take us into the realm of mirror neurons, a story for another day.

[2] This connection is talked about in Walter Mischel’s 2014 book entitled The Marshmallow Test: Why Self-Control Is the Engine of Success.

[3] Interestingly, Goldberg points out that even though Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and PTSD do have certain symptoms in common, the brain centers involved are different.