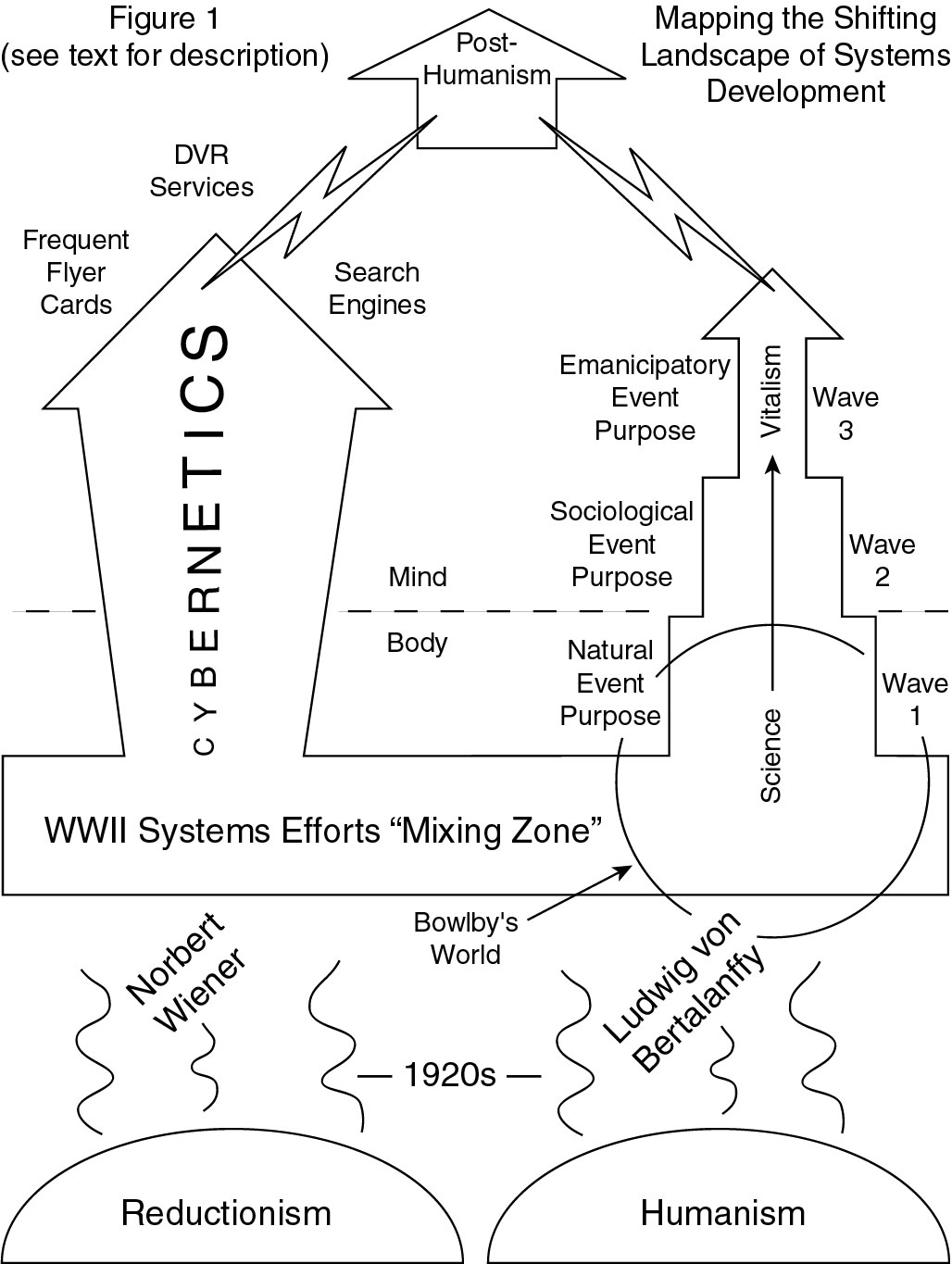

How is it that we find ourselves in the swimming pool of the cyborg—part human, part machine—inching our way toward the deep end? In her 1999 book entitled How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics, Katherine Hayles asks a similar question: “How is it possible in the late twentieth century to believe, or at least claim to believe, that computer codes are alive—and not only alive but natural?” Hayles continues thus: “The question is difficult to answer directly, for it involves assumptions that are not explicitly articulated. Moreover, these presumptions do not stand by themselves but move in dynamic interplay with other formulations and ideas circulating throughout culture.” I agree with Hayles when she suggests that the emerging cyborg or cybernetics landscape is incredibly complex. Faced with such complexity I always find it easier to navigate such terrains by creating a map that not only shows certain trends but also the relationships between these trends. I created such a map for my 2011 book entitled Bowlby’s Battle for Round Earth: Summaries of Bertalanffy & Midgley Revealing the Systems – Attachment Theory (Dis) Connection. Below is that map.

At this juncture it is not important that you understand what is being depicted above. I’ll cover the meanings and relationships depicted as we go along. Suffice it to say that my map generally agrees with the information that Hayles presents in her book. Given that science enjoys independant corroborating evidence, I should point out that I read Hayles’ book for the first time after I wrote Bowlby’s Battle and sketched out the above map.

In reading Hayles’ book I was pleasantly surprised to discover that we were both heavily influenced by what are known as the Macy conferences. In many ways, the Macy conferences set the stage for what surrounds us now: iPhones, AI or artificial intelligence, self-driving vehicles, virtual worlds, the Internet, big data, social media, and the list goes on. In many ways, the Macy conferences built the cyborg pool that we now find ourselves swimming in. It would be hard if not impossible to make sense of the cyborgism or cybernetics that surrounds us without spending some time reviewing the Macy conferences. Now, there’s a bit of a “behind the scenes story” to the Macy conferences that I would like to tell you first if you would indulge me.

The Wikipedia entry for the Macy conferences defines them thus: “The Macy conferences were a set of meetings of scholars from various academic disciplines held in New York under the direction of Frank Fremont-Smith at the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation starting in 1941 and ending in 1960.” The Wikipedia entry continues, “The explicit aim of the conferences was to promote meaningful communication across scientific disciplines, and restore unity to science.” Apparently there were 160 conferences over a span of nineteen years. These conferences covered myriad topics including child psychology, medicine, anthropology, Gestalt psychology, psychodynamics, neurology, robotics, group processes and dynamics, and on the list goes. (See the Wikipedia entry for a full listing of topics covered.) However, the lion’s share of the conferences were on cybernetics. Norbert Wiener, often considered the father of cybernetics, offers up this definition of cybernetics: “The science of control and communications in the animal and machine.” In addition, many of the other conferences brought their findings back to the realm of cybernetics. As an example, the following topic was covered at a 1952 conference: The Relation of Cybernetics at the Microlevel to Biochemical and Cellular Processes.

Before I read Hayles’ book, I had very little knowledge of the Macy conferences proper. Turns out that there was a second set of “Macy conferences” that were held in Geneva from 1953 to 1956. Apparently these Geneva conferences were supported by the World Health Organization (as opposed to the Macy Foundation) and patterned after the Macy conferences. In fact, Frank Fremont-Smith, director of the New York conferences, played a role in organizing the Geneva conferences. Do you know who else played a role in organizing the Geneva conferences? Yes, John Bowlby. It was through my study of John Bowlby that I discovered his participation in the Geneva conferences, which, in turn, have a connection to the Macy conferences. And, yes, several scientists and researchers presented at both the New York and Geneva conferences. Examples here would be the aforementioned Fremont-Smith, Margaret Mead (cultural anthropology), and W. Grey Walter (electrophysiology and robotics). I should mention that the Geneva conferences also featured such luminaries as Jean Piaget (developmental and cognitive psychology), Konrad Lorenz (ethology), Julian Huxley (evolution theory and biology), Erik Erikson (psychoanalysis), Ludwig von Bertalanffy (systems theory, biology, and evolution theory), and of course John Bowlby.

Whereas the Macy conferences were centrally focused on cybernetics, the WHO conferences were centrally focused on topics such as evolution, biology, organic systems theory, ethology, and developmental psychology. It should come as no surprise that Bowlby’s work following the WHO conferences—as evidenced by his three volumes on attachment theory—is shot through with these same themes: evolution, biology, developmental psychology, and ethology or the study of animal behavior. It could be said, arguably, that the Macy conferences birthed cybernetics while the WHO conferences birthed Bowlbian attachment theory. Thus the above systems map has cybernetics and the early influence of the Macy conferences on the left side while the right side reflects the influence of the WHO conferences and their focus on organic systems, evolution, biology, and developmental psychology. Even though I have depicted a division, keep in mind that there was cross-pollination between the two sides. As an example, according to Hayles’ research, the early days of cybernetic thinking were greatly influenced by the idea of homeostasis—keeping organic systems within certain optimal parameters—which is a concept borrowed from organic systems theory. Similarly, Bowlby, in his work, would use radar guided antiaircraft gun systems—an example of mechanical cybernetic feedback systems—to bring attention and understanding to the organic behavioral systems, like attachment, that he was studying.

Hopefully I have succeeded in setting the stage for what is to come in the next posts. As alluded to above, the “shifting landscape of systems development” as I call it, is incredibly complex. Further, Hayles is correct in pointing out that much of this landscape is hard to grasp because it “involves assumptions that are not explicitly articulated.” As an example, Bowlby, in his work, would often use concepts clearly drawn from organic systems theory while never (that I could find) explaining these concepts or making reference to their source (which, I’m assuming, is von Bertalanffy’s work in many cases). As a result of this complexity, we are left to paint pictures using broad brushstrokes. However, it is my feeling that broad brushstrokes are necessary to get us to where we need to go because falling off into the weeds of detail would certainly lead to not being able to see the proverbial forest for the trees. This being said, let me end this post with a rather large brushstroke.

In preparation for writing this post I went back and reread Hayles’ book for the third time. Trust me, I get something different from Hayles’ book with reach read. This time what impressed me was the source or the “magma chamber,” if you will, driving the tectonic shifts taking place within this complex systems landscape. My map shows “humanistic thinking” as one source, but it’s bigger than that. As Hayles points out, the very definition of what it means to be human is in play throughout the systems landscape. As an example, Hayles observes, “[T]he cybernetic machine was to be designed so that it did not threaten the autonomous, self-regulating subject of liberal humanism.” Pulling from work by Otto Mayr, Hayles continues, “Mayr argues that ideas about self-regulation were instrumental in effecting a shift from centralized authoritarian control that characterized European political philosophy during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (especially in England, France, and Germany) to the Enlightenment philosophies of democracy, decentralized control, and liberal self-regulation.” Here’s Hayles’ bottom line: “Because systems were envisioned as self-regulating, they could be left to work on their own—from the invisible Hand of Adam Smith’s self-regulating market to the political philosophy of enlightened self-interest.”

Hayles is of course talking about the huge cultural shift from the centralized control of religion to the decentralized control of the self. It would take us too far afield, however, what we are looking at here is the shift in what researchers call “cultural cognitive models.” For more on this theme, see the 1996 book Changing Visions—Human Cognitive Maps: Past, Present, and Future by Ervin Laszlo and his colleagues. Taking my cue from McGilchrist’s book The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, in my mind, this represents the psychological shift from control by middle brain systems to control by the Executive Functions of the upper brain. (I covered EF in some detail in my previous blog series Executive Function and the Art of Diesel-Powered Car Repair.)

There’s only one problem: Who gets to embody this new liberal definition of what it means to be human? Commenting on the work of Norbert Wiener, Hayles suggests that “[h]is writing indulges in many of the practices that have given liberalism a bad name among cultural critics: the tendency to use the plural to give voice to a privileged few while presuming to speak for everyone; the masking of deep structural inequalities by enfranchising some while others reman excluded; and the complicity of the speaker in capitalist imperialism, a complicity that his rhetorical practices are designed to veil or obscure.” Hopefully the reader will notice that these criticisms of liberalism foreshadow the rise of the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) movement, which we will look at in future posts.[1] In the next post, we will look at how each area of the changing systems landscape is trying to define what it means to be human.

NOTES:

[1] In case the reader is not familiar with the DEI movement and the controversies surrounding it, here is a link to a USA Today online article entitled What Does a DEI Ban Mean on a College Campus? Here’s How It’s Affecting Texas Students.

https://www.yahoo.com/news/does-dei-ban-mean-college-093129640.html