In the last post, I ended by mentioning that the Enlightenment ushered in a new conceptualization of what it means to be human. According to Hayles’ research, liberal humanism conceptualized the human as being free, autonomous, self-regulated, and self-directed. In my mind, liberal humanism seems to be describing a person who is able to access the Executive Functions of the upper brain such as empathy, perspective taking, mental time travel (like imagining the future and having hope), delaying gratification, focusing attention, regulating emotion, etc. Neurobiologist Antonio Damasio in his work suggests that the extended consciousness that can be accessed by accessing the upper brain most likely allowed for the development of such things as fine art, literature, music, and theater. ADHD (attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder) expert Russell Barkley suggests that access to the upper brain and its EF skills allowed for the development of such things as systems of ethics, morality, and law. Barkley uses the example of Do unto others as you would have them do unto you to show thought coming from the upper brain. Come to think of it, when Jesus told his disciples the various parables for which he is known, Jesus was in fact encouraging his disciples to enter the realm of the upper brain. Dr. Martin Luther King did the same thing when he made his I Have a Dream speech.

I’ve used the following quote before, however, I think it is appropriate here as well. Louis Cozolino writes in his book The Neuroscience of Human Relationships (pulling from work by Schall), “Without the ability to reflect, imagine alternatives, and sometimes cancel reflexive responses, there is little freedom from being a biological machine reacting to the environment.” In essence Cozolino is suggesting that access to the upper brain and EF skills frees us from the tyranny of the middle brain, which, before the Enlightenment, was represented by the rule and authority of the Catholic Church.

It would seem that the age of Enlightenment should usher in unbridled peace, prosperity, and happiness. In addition, liberal humanism would assure that the invisible Hand of Adam Smith’s self-regulating market would have very little work to do. Well, this did not happen. As social critics point out, many were not able to enter the realm of the upper brain. Pulling from the work of Barkley, there are many reasons why a person may not be able to access the realm of the upper brain: genetic factors, environmental toxins, brain trauma such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), and psychological trauma as might be brought about as a result of natural disasters, cultural oppression, genocide, or even war.

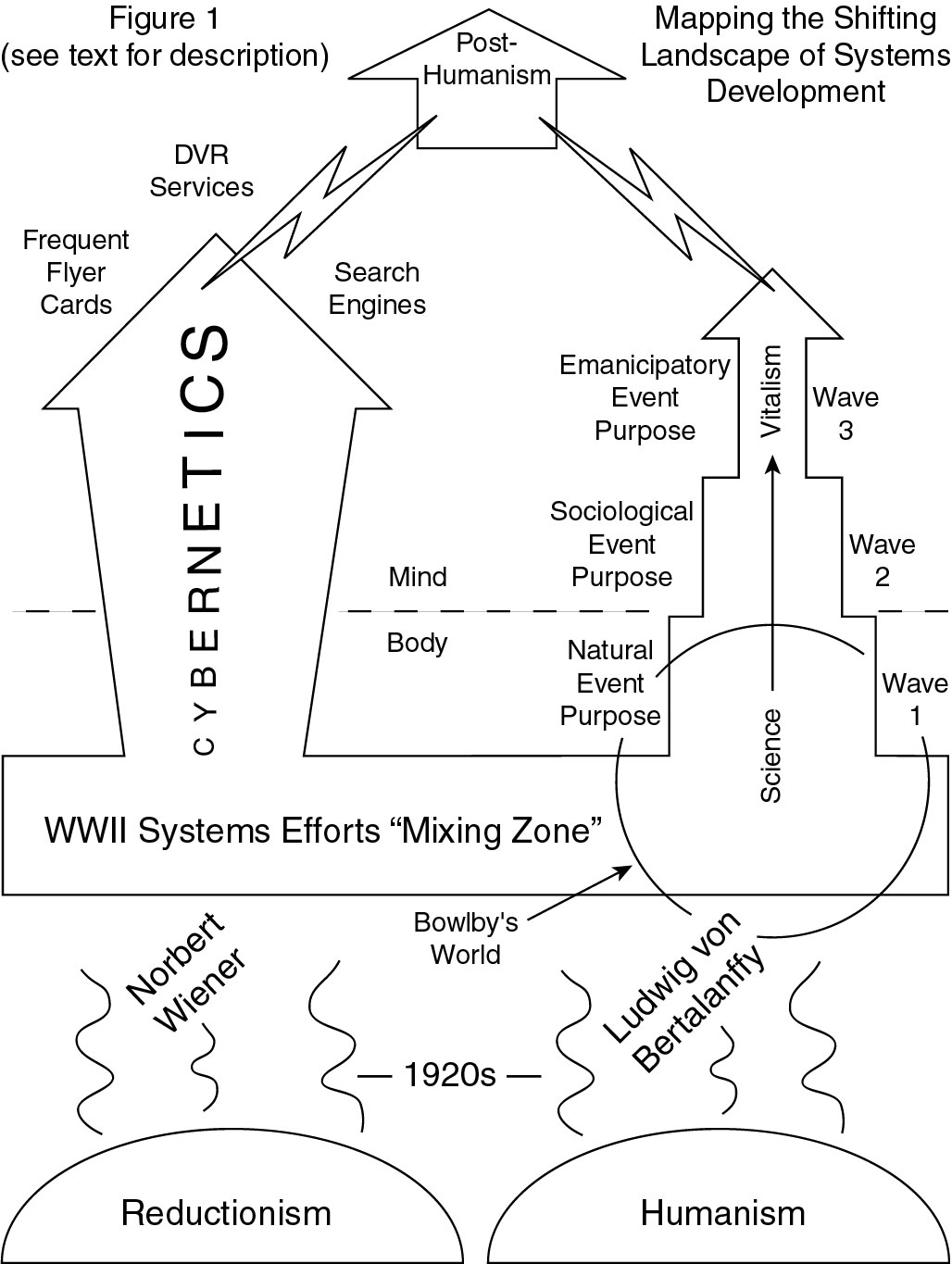

As a result of WWII, people all over the world were subjected to insane levels of trauma on a multitude of levels. Heck, the U.S. dropped the first atomic bombs on the people of Japan. Our collective psychology changed forever as the possibility of destroying planet Earth became a reality. I still remember having to get under my desk as a child during school drills designed to protect us from a nuclear attack (like that would work). So, it is no wonder that in their own ways, myriad groups, following the close of WWII, tried to assess how the tsunami of trauma sweeping the Earth would affect people, and, specifically, their ability to access the realm of the upper brain. Recall that Bowlby was asked by the World Health Organization to survey the level of psychological damage that may have been done to the thousands of orphans roaming the streets of London in the aftermath of WWII. In many ways my map of the shifting systems landscape tries to conceptualize these efforts and their outcomes. Here’s my map once again for your convenience.

Allow me to sketch out what is going on in each of these areas.

According to Hayles’ research, information scientists, such as Norbert Wiener, Claude Shannon, and John von Neumann—scientists who gave birth to cybernetics chiefly through their participation in the Macy conferences—were concerned about liberal humanism and how it conceptualized what it meant to be human. Again, liberal humanism conceptualized the human as being free, autonomous, self-regulated, and self-directed. These information researchers were also acutely aware that, for whatever reason, many may not be able to access the Executive Function skills of the upper brain such as being self-regulated and self-directed. As a result, they set out to hopefully solve this problem. What they came up with is, on the surface, rather shocking.

As Hayles chronicles in her book How We Became Posthuman (pulling largely from the transcripts of the Macy conferences), these information scientists began wondering if information needs to be embodied. Looked at another way, they wondered if information can exist outside of a body or any form of embodiment. In essence, these information scientists were contemplating the possibility of “pure information,” information that exists outside of any form of embodiment.[1] Hayles cautions us against dismissing this idea without reflection by pointing out that a writer (such as myself) effectively puts his, her, or its thoughts into the form of a code (written language) that exists on some medium. After I write these words they exist on a computer chip inside my laptop. Clearly since the times of cave drawings thousands of years ago, humans have been able to embody their thoughts within different media. But what about pure information, information that exists outside of any discernible medium, is this possible?

Information scientists suggested that, yes, pure information could exist. They then argued that once information could be put into a pure form, it could then be put into any form of body or embodiment one desired. Thus was born the founding idea of cybernetics and along with it the cyborg. As indicate above, cybernetics and the cyborg have moved ahead getting larger and larger until now we are encouraged to embrace all manner of AI or artificial intelligence, ChatGPT being a prime example here. Cybernetics holds out the promise that one day we can simply download our brains into a new mechanical form, or even exist “purely” in cyberspace. Through the “downloading” process we can realize the liberal humanist dream of being self-regulated and self-directed. Before you laugh, you may wish to take note of your iPhone, your laptop, your social media, and all of the “data exhaust” you dump into big data reserves on a daily basis. You are becoming posthuman as Hayles and others suggest. At the very least, you are very much in the cyborg pool.

From my psychological standpoint, when I hear about talk of “disembodied information,” I immediately think of dissociation—the linear left brain dissociated from the holistic or body-oriented right brain. I also begin thinking of trauma because trauma is one way the left brain can become dissociated from the right brain. I also begin thinking about the huge amounts of trauma that have occurred within this and the last century. For this reason, is it possible that information science is a trauma narrative? If the answer is “yes,” then the next question becomes, Is this a trauma narrative that has the ability to bring healing to the masses? To answer these questions, let’s look at how thinking about cybernetic systems progressed during the Macy conferences.

The idea that homeostasis should influence the formulation of cybernetic systems was jettisoned early on. Information scientists then imagined cybernetic systems in terms of “recursion” or “reflexivity.” Here’s the informal definition that Wikipedia provides for recursion: “Recursion is the process a procedure goes through when one of the steps of the procedure involves invoking the procedure itself. A procedure that goes through recursion is said to be ‘recursive.’ ” I gave you the informal definition because, frankly, the formal definition is a head scratcher. Wikipedia continues thus: “Even if it is properly defined, a recursive procedure is not easy for humans to perform, as it requires distinguishing the new from the old, partially executed invocation of the procedure; this requires some administration as to how far various simultaneous instances of the procedures have progressed. For this reason, recursive definitions are very rare in everyday situations.” So, yes, even though “recursive definitions” are rare, they were being used as a model for the development of the cyborg which, in turn, was being used as a way of redefining what it means to be human.

Hayles points out that such ideas as “disembodied information” and “recursion” troubled psychoanalysts attending the Macy conferences to the point that they considered an intervention fearing for the psychological sanity of these information scientists. “The Macy participants were right to feel wary about reflexivity,” writes Hayles. She continues, “Its potential was every bit as explosive as they suspected.” When you think of recursion, think of the image of the Ouroboros, a snake eating its own tail:

Image by Gustavo Rezende from Pixabay

Recursion was also jettisoned and gave way to recursion but with a direction. According to information scientists, recursion with a sense of direction added to it, in effect, creates a spiral. Suffice it to say that “recursion with direction added” was the foundation that built no only the cyborg pool, but also placed most of us in that pool. Again, is all of this a trauma narrative supported by dissociative thinking? And if so, does it have dynamic stability, the kind of stability that will bring us back to integration and healing. Or will its “direction” send us rocketing toward the sun, the same sun that sent Icarus to his doom? I think these are questions that should concern us all because in the very short span of 70 years or so, we have gone from the birth of information science to ChatGPT and other forms of AI in essence doing our thinking for us. Heck, a colleague mentioned that her place of business uses an email server with AI software installed that can write entire email messages based on a couple of words. Yeow! Maybe AI is writing this post….

There’s a bit more to this story, which we will get to later. In the next post I’d like to move to the other side of my map and look at the progression from organic systems, to sociological systems. For this we will be looking at the work of Ludwig von Bertalanffy and Gerald Midgley (as talked about in my book Bowlby’s Battle). We’ll wrap up this series by looking at emancipatory systems.

NOTES:

[1] When I think of “pure information,” I think of the philosophical question: If a tree falls in the woods, does it make a sound? What this question asks is, For sound to exist, do we need an organic entity of some sort to receive the physical waves generated, and then convert those waves into the experience we call sound? In essence, without the organic sensing entity, sound remains at the systems level of physical waves. So, if information falls in a forest, does it make meaning?

Drawing from a course I took in remote sensing, yes, there is information all around us. As an example, rocks on distant planets absorb certain wavelengths of electromagnetic (EM) radiation and reflect others. This allows scientists on Earth to scan distant planets using satellites equipped with EM scanners and in doing so, determine the composition of the surface of a distant planet. Pretty cool! That EM “information” is there whether an organic entity of some kind receives it or not, whether an organic entity makes meaning out of it or not. Sure, there is “pure information,” however, the very concept or the very meaning of pure information was devised by an organic entity, that is to say, humans. This brings up the mistake that Descartes made (and is talked about in Antonio Damasio’s book Descartes’ Error).

When Descartes issued forth with his now famous dictum Cogito Ergo Sum (I think therefore I am), he makes a very basic and logical mistake. In order for Descartes to even think, let alone speak, the words Cogito Ergo Sum, those words would have to exist. In other words, his thinking does not represent some pure state. Descartes conveniently forgets about, well, the entire evolutionary history that allowed his brain to exist let alone think the words Cogito Ergo Sum. And as Hayles points out, information scientists, not unlike Descartes, wished to correct the mistake of evolution and get to pure states. “It is no accident that evolution is a sore spot for autopoietic [i.e., self-making] theory,” observes Hayles, “for the theory was designed to correct what [information scientists] Maturana and Varela saw as an overemphasis on evolution.” In many respects, information scientists wished to throw evolution out the window and start afresh using what I would call mildly a “god complex.” Many in the scientific community wonder how it is that evolution is under attack these days. (See my blog series Beyond Thoughts & Prayers for more on this theme.) Part of the cause can be traced back to the beginnings of information science. And certain religious groups are more than happy to join these attacks against evolution. Intelligent design and creationism (along with the creationist center at the Grand Canyon) are but two examples. This pile-on against evolution should raise a red flag, especially when it comes to efforts that purportedly wish to save the Earth given that the Earth literally records our history from the proverbial primordial soup until today.

These errors in thinking, in my opinion, describes what I would call “dissociative thinking” or “trauma thinking.” But what trauma? In his book Looking for Spinoza, Damasio talks about how it was common for families in Spinoza’s time (the mid-1600s) to gather in the village square and watch horrific examples of trauma such as human torture and burnings. The same was true for Descartes. Both philosophers either directly experienced or heard about horrific forms of trauma. I would suggest that this history of trauma greatly influenced Descartes’ thinking. Yes, trauma and dissociation have played big roles in the development of culture.[2] I applaud Dr. Pynoos’ efforts (talked about in Pt 2) to bring attention to this fact. As talked about earlier, this is why it is so important to bring about collective healing following collective trauma.

Did the founding fathers of information science make the same mistake, the same error Descartes made? And why would any group of people follow a trauma narrative that does not bring about healing? After trauma, people are looking for any, and I mean any, narrative that might make sense out of that trauma. This in part may explain why the German people were so ready to follow Hitler after the defeat of WWI and the economic constraints imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Are we following the “information trauma narrative” because of the horrific traumas of WWII, the Korean War, Vietnam, the Middle East conflicts, the Israel/Hamas conflict, the Ukraine/Russia conflict, and the huge ledger of cultural oppression that exists here in the U.S.?[3] Are we following the information trauma narrative into the abyss seeking healing but finding more destruction? It does not escape my thinking that I am typing on an information device, and that, more than likely, you are using one to read this post. Man O Man … the water in this cyborg pool is getting awfully warm.

For more on trauma at the level of large groups, even countries, see the 2023 edited volume that I just started reading entitled We Don’t Speak of Fear: Large-Group Identity, Social Conflict and Collective Trauma, which looks at collective trauma from a psychoanalytic (as well as legal, social, and political) standpoint. I should point out that several of the efforts talked about in this book took inspiration from the psychoanalyst, Erik Erikson, who, as we saw above, participated in the Geneva conferences. Did Erikson influence Bowlby in the area of ToTT or transgenerational transmission of transmission of trauma? Very likely. Let us not forget that Bowlby spent many years as a psychoanalyst before venturing into the realms of ethology and organic systems theory.

[2] For more on this theme, see the 2011 book by Nassir Ghaemi, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, entitled A First-Rate Madness: Uncovering Links Between Leadership and Mental Illness.

[3] In the edited volume entitled We Don’t Speak of Fear: Large Group Identity, Social Conflict and Collective Trauma, Lord John Alderice writes, “Is it possible that some of [the] historical construction of the personality of the United States has not yet been fully addressed and processed and that when America spreads its civilizing influence around the world, it does so with an unconscious negative underlying flavor drawn from this history of not so long ago.” He continues, “Whatever the truth or otherwise of this speculation, the observation about the sometimes brutal origins of the United States makes it clear that dehumanization is not a mechanism that we can locate only in those people and places where terrorist activity takes place.” Alderice is in fact making the same point that Chalmers Johnson makes in his 2001 book entitled Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire. Is not cyborgism a form of psychological imperialism? By analyzing works by science fiction writer Philip K. Dick and others, Hayles tackles this question in her book How We Became Posthuman.